Release 02 01 Nov 2025 WorkingDoc

TL:DR

Recent developments in academic analysis and case law suggest that United States copyright does not generally extend to published implementations of commonplace numerical algorithms.

This post explains why by invoking the merger doctrine, now one of the three mainstays of copyright law in the United States.

The Simplex method code published in the 1992 edition of Numerical Recipes by Oxford University Press is used as an example.

Introduction

The numerical algorithms under consideration often form the core of numerical analysis. Notable examples include Newton’s method to identify the zero‑valued roots of differentiable functions. And the field of linear programming, used to find optimal solutions to sets of under‑constrained linear relationships and some given measure of betterment.

Contemporary open‑source software is not affected by these copyright dilemmas. There are now excellent open-source numerical libraries, such as the GNU Scientific Library (GSL), which are both mature and high-performing. Indeed, some of these projects were explicitly initiated in response to the legal concerns under discussion here.

Matters of legal uncertainty regarding software copyright in numerical algorithms are more relevant for legacy codebases that drew on code distributed publicly in an earlier era. But some questions do persist, including questions directed towards academic publishers who continue to sell restrictive licenses for source code that is unlikely to be subject to the copyrights they claim.

This post uses the Simplex method code from the 1992 edition of Numerical Recipes as a case study (Press et al 1992). I argue that this implementation should class as public domain. My assessment draws on the merger doctrine from United States copyright law which prevents substantially functional elements from receiving protection. This result can possibly be generalized to cover all the source code provided in the Numerical Recipes series.

Please note that I have no legal training. An experienced open‑source lawyer from the United States reviewed an earlier version of this post favorably. I also received valuable input from the FSFE legal community on specific technical questions. I am grateful for these contributions, which were made voluntarily.

Context

This post was developed because the open‑source status of the deeco codebase was contested in an email I received in late‑May 2025. Having contributed to and later maintained deeco over eight years, I have a material interest in this matter. deeco was licensed under the GNU GPLv2 in 2000 and made available the following year.

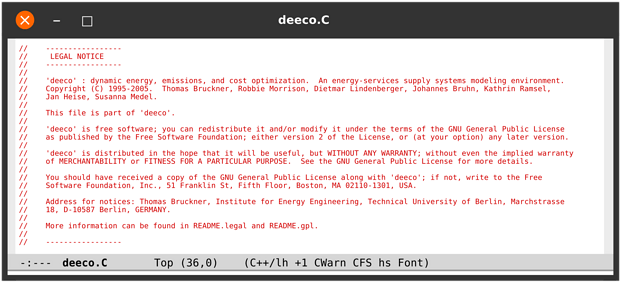

Fig 1: A license notice from the deeco codebase added in 2000 (and periodically updated)

deeco was an early high‑resolution contiguous‑time energy system modeling environment or framework. Most such frameworks are intended to explore rapid and complete decarbonization and almost all have their roots in academia.

One of the key claims in that email was that deeco included a “proprietary library” from a Numerical Recipes publication, meaning that deeco cannot therefore be classed as open‑source. Although there is no consensus definition for the term proprietary software, it is often taken to refer to closed‑source software. Hence, the source code published in Numerical Recipes would not usually be described as proprietary. And nor would it normally be considered a software library in the sense of maintained and packaged code by even the standards in 1992.

Notwithstanding, a legitimate legal question remains regarding the inclusion of modified Numerical Recipes source code within deeco. And specifically the question of whether the implementation of the Simplex method in Numerical Recipes (hereafter “simplex code”) is protected by United States software copyright. If so, it would not be legitimate to describe deeco as open‑source.

This post argues that the simplex code in question is not protected by United States intellectual property law.

I am not invoking the United States legal doctrine of fair use here because that would not entitle me to add a public license to deeco and then offer that codebase to third parties. Fair use is an affirmative legal defense that must normally be established by the user on a case‑by‑case basis. I am arguing instead that the Numerical Recipes simplex code is necessarily public domain.

Thomas Bruckner wrote the deeco energy system modeling framework in the C++ language for his PhD, completing the initial program in 1995. I ported the codebase from a Hewlett-Packard workstation to Intel hardware in 1998 and was later the project maintainer for eight years.

Dr Bruckner also found a corner‑case bug in the Numerical Recipes simplex code. He communicated with the chapter authors on the matter and provided them with a small patch. This interaction certainly aligns with the ethos of open‑source software development.

I have a clear interest in arguing that the Numerical Recipes source code is indeed public domain. But I also want to work to academic standards and would willingly concede that code taint had occurred if I believed that to be the correct interpretation.

Only a court can conclusively determine the presence or absence of copyright in a particular work, including source code. And while similar-fact case law can be informative, there is relatively little direct litigation of close relevance in this context. This means that a level of professional judgment is required, as is often the case with civil conduct that has not been extensively litigated.

There are various views on how the copyright status of software should be interpreted, ranging from risk‑averse to transactional. I contend that the standard set by the open source community for license compliance analysis is the appropriate benchmark to use (Wintersgill et al 2024). This standard attempts to align with the kinds of determinations a civil court could make in similar circumstances. Meeker (2025:63–68, 142–145) makes the same case, but extends her analysis to consider litigation risk under the rubric of “legal realism”, which then lowers the bar on the assumption that legal action is often not forthcoming.

In regards terminology: “deeco” may refer variously to the deeco codebase, the wider deeco ecosystem, or the deeco project overall. As indicated earlier, the stub “simplex code” is a placeholder for the Simplex method C source code published in the second edition of Numerical Recipes in C (Press et al 1992:430–444).

Numerical Recipes solver code

deeco uses 180 short lines of source from Numerical Recipes in C. For which publisher Oxford University Press (OUP) claims sole copyright and sells restrictive direct licenses. OUP also provides some minor concessions for use by individuals which might well be covered by fair use considerations in any case. I did not examine these potential exceptions, nor are they relevant here.

The section covers the core arguments, while a later section delves into the underpinning legal theory in more detail.

Under copyright law, the only party with the standing to bring suit is normally the presumptive copyright holder — in this case, Oxford University Press. And, in the first instance, the burden of persuasion rests with the party who initiates a claim using the standard of proof set for civil litigation. That litigation will often never happen of course in the case of deeco, but these courtroom obligations and the way they might fall can help guide this discussion

My analysis relies on the legal constructs current in 2025 because that is how such a claim would be litigated today. The year 2025 also offers the advantage of substantially more software‑related case law and legal analysis than back in 2001 when deeco was made available under the GPLv2 license. United States law is also applied because Numerical Recipes was printed in the USA. The textbook in question is:

- Press, William H, Brian P Flannery, Saul A Teukolsky, and William T Vetterling (30 October 1992). Numerical recipes in C: the art of scientific computing (2nd ed).

My core premise is that copyright is highly unlikely to be present in the simplex code copied into deeco and that I can reliably treat that code as public domain. My reasoning is that the code in question does not meet the thresholds for originality and creativity required by US copyright law. My principle line of argument employs the merger doctrine as follows:

- that the simplex code does not attract copyright because it implements a commonplace algorithm such that the underlying ideas and their expression in code merge to the point where that expression is no longer eligible for protection under US law

I also contend (as noted in the introduction) that these legal questions should be treated as practical cases of copyright and license compliance — as deployed in the open source world. And not be subject to some remote possibility that some theoretical court could rule in favor of copyright being present after a hypothetical plaintiff had provided a suitably narrow case. In other words, reason and caution should apply in favor of open source and open science.

There is a clear trend for the public to treat all seemingly intellectual or creative outputs as protected by copyright. And a discernible trend in the opposite direction in which courts are simultaneously clarifying and raising the legal thresholds for such protections (setting aside the current wave of AI‑related litigation which has yet to be conclusively adjudicated). Indeed, a good number of copyright claims are either rejected by the US Copyright Office or fail later in court. I am not aware of any case law that covers academic software, which is perhaps not surprising.

To be clear (as noted in the introduction), I am arguing that copyright does not apply in the particular circumstances under discussion and not that some legislated exception or affirmative fair use defense might apply. That is not to say that these other considerations have no merit in this context, just that I am not deploying them. Moreover an assessment of fair use is difficult in the absence of similar fact case law (Meeker 2025:140).

I am going to look at the historical setting too. Recognition of copyright, open‑source licensing, and the norms of community development evolved strongly over the period that deeco was an active project between 1992 and 2006. Fast forward to today and I would not have left the simplex code in contention in a codebase I was open sourcing. Nor would that have been remotely necessary, given the number of serviceable open‑source solver libraries now available.

The legal and social aspects of open‑source development are separate in the sense that a codebase may be legitimately open‑source in the absence of any attempt to build a surrounding community. This strategy, sometimes described as “dump and run” has a place, for instance when archiving source code in support of published research.

The social aspects of the deeco project are considered in a separate post.

Historical context

Copyright‑informed open source development is a relatively recent phenomenon. The following table places deeco in an historical context.

These events show that the development of deeco was largely contemporaneous with the initiation, uptake, defense, and legal legitimization of the groundbreaking GPLv2 suite of open‑source licenses (noting that the GLPv1 was short‑lived and rarely used). These events also demonstrate that the open source concept emerged in response to software being formally included in copyright law and then increasingly recognized as intellectual property. The open source concept was also necessarily subject to development and evolution.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1966 | Künzi et al (1966) optimization textbook published in German |

| 1968 | Künzi et al (1968) optimization textbook translated into English |

| 1976 | major revisions to the US Copyright Act |

| 1978 | those revisions take effect with explicit copyright notices no longer required |

| 1980 | US Copyright Act extended to cover computer programs, effective immediately |

| 1982 | the concept of merge introduced by US case Apple v. Franklin Computers |

| 1985 | Federal Republic of Germany amends copyright law to include computer programs |

| 1986 | Press et al (1986) Numerical Recipes textbook first published |

| 1991 | EU software directive 91/250/EEC harmonizes member state law |

| 1991 | Richard Stallman releases GPLv2 license |

| 1992 | Press et al (1992) second edition published |

| 1995 | deeco codebase completed (but with no public license) |

| 1996 | Linus Torvalds releases prototype Linux kernel under GPLv2 |

| 1998 | Open Source Initiative (OSI) formed to promote open source software |

| 1999 | Eric Raymond publishes widely read Cathedral and Bazaar |

| 2000 | GPLv2 license added to deeco |

| 2001 | deeco codebase made available on CD-ROM |

| 2001 | deeco website launched |

| 2001 | deeco SSH server established to provide remote execution and development |

| 2002 | Creative Commons 1.0 suite released |

| 2004 | German programmer Harald Welte initiates gpl-violations.org GPL compliance project |

| 2006 | deeco project abandoned after C++ programming libraries stranded |

| 2007 | Software Freedom Conservancy (SFC) begins pursuing BusyBox GPL non‑compliance |

| 2007 | GPLv3 released by the Free Software Foundation (FSF) |

| 2010 | Jacobsen v. Katzer ruling that OS licenses can be enforced under US copyright law |

| 2012 | SAS v. World Programming that source code attracts copyright under EU law |

| 2017 | deeco codebase archived on GitHub for historical purposes |

| 2018 | McHardy case in Germany concluded that European courts recognize GPLv2 |

| 2025 | today |

| 2050 | hypothetically looking back in 25 years time on today’s practices |

Some observations follow. In the United States, software was not considered protectable under copyright law until the passage of enabling legislation in 1980 (Lemley 1995:5–6). Therefore the early publishers of source code libraries, in all probability, did not intend that their work would be protected. Prior to the effectiveness of the 1976 US Copyright Act, anything published without an explicit copyright notice could fall into the public domain. Due to the gradual increase in copyright term lengths and the relatively recent emergence of software, virtually no software has entered the public domain through copyright expiration thus far.

Following the 1980 change in US law, legal clarity concerning software copyrights emerged slowly through a sequence of civil judgments. Lemley (1995:6) writes:

Even after the 1980 amendments, establishing copyright protection for the literal text of computer programs was a protracted process.

The Open Source Initiative (OSI) was established in 1998 to promote the uptake of open source software and deeco was licensed under the GPLv2 two years later. The Creative Commons suite of licenses were first released in 2002, one year after the deeco SSH secure shell server and website were launched in 2001.

Legal clarity regarding the status of open-source public licensing was also slow to develop. Key judgments confirming the recognition of such licenses under US copyright law first arose in 2010.[1] But only with the McHardy judgments from various German courts concluding in 2018 was it clear that the GPL family of licenses would be unequivocally enforceable in Europe.[2] A lag of 18 years for the deeco codebase.

Back in 2000, no one understood or talked about copyright in relation to research software. As I recall, there was no discussion on the fact that code from Numerical Recipes could not be freely used. An internet search today will reveal similar sentiments and resigned criticism regarding the software policies that Oxford University Press chose to adopt in this context and continues to deploy.

Looking back from 2050 to today is a useful exercise and not as hypothetical as may seem. The pending judgment for SFC v. Vizio [3] may upend four decades of legal theory in respect of open source licensing and lead to a new round of civil litigation framed under contract law and not copyright law — in which users as well as developers will have legal standing (Meeker 2025:9,308–309).

Some internet anecdotes

I found some historical observations on the Numerical Recipes series on the internet that I think are worth repeating:

NelsonMinar writing on 3 April 2022 on code development (ycombinator)

It’s worth putting this book in historical context. It was first published in 1986. Numerical programming like this was very much a black art and the book was an well researched, documented, usable set of algorithms with (mostly) working code. Open source code was a very new idea (FSF was only established a year before, and while there are earlier precedents like BSD source it was all very new.) Source code distributions were awkward; absolutely nothing like github of course, just a few FTP servers which maybe you could get code from if you knew they existed and had Internet access. Typing in code from a book seemed perfectly reasonable.

And sbrorson writing on 3 April 2022 on software licensing (ycombinator)

The real complaint made in the linked post involves the licensing terms of the code in NR. I agree the license stinks by today’s standards. But the book was originally written back in the 1980s. My copy is from the early 1990s. Back then the GPL was basically unknown outside of a group of happy hackers at MIT. Software licensing certainly not a topic occupying mindspace of ordinary scientists or engineers. There was some DOS-based “freeware” circulating on 3.5" disks, but the whole “free (libre) software” movement was still in the future – it needed the internet to become widespread in order to take off. Finally, I can imagine the NR authors wanted some sort of copyright or license which prevented wholesale copying of their work by folks who would try to profit off it. It’s reasonable for them to have wanted to get some monetary reward for their hard work. Their license is probably an artifact of its time.

Numerical Recipes solver code revisited

Skip this section if you don’t wish to drill down into US copyright law and the inner workings of numerical software.

The key issue here is under what circumstances might a block of source code from a textbook on numerical methods attract copyright. This discussion is about the presence or otherwise of copyright, not whether statutory exceptions for research and education or affirmative defenses including fair use might apply.

Recall that the applicable law is United States law because the Numerical Recipes textbooks were printed in the United States.

The merger doctrine under US copyright law

The US Library of Congress Congressional Research Service describes the three major doctrines that underpin US copyright law: the idea/expression dichotomy, the merger doctrine, and fair use (Hickey 2021). The Research Service explains:

The second doctrine, known as merger, is a corollary to the idea/expression distinction. When there are only a few ways to express an idea, the expression is said to “merge” with the idea, and neither is copyrightable. Otherwise, copyright could protect all of the few ways to express the idea, which would effectively monopolize that idea while the copyrights last. One central purpose of both the idea/expression distinction and merger is to prevent the use of copyright to monopolize general ideas or functional systems. Unlike books or television, however, computer programs primarily serve functional purposes, which complicates applying the idea/expression distinction.

The merger doctrine is pivotal to the arguments presented here. However, the academic literature covering its application to software is limited. I relied primarily on Samuelson (2016b), Malson (2019), and material from the US Library of Congress (just quoted).

Unlike the idea/expression dichotomy, which is codified in §102(b) of the US Copyright Act, the merger doctrine arises from judge‑made law with its roots in Apple v. Franklin Computer decided in 1982 (Samuelson 2016b:4).[4] Historically, the notion of separation of ideas from expressions was first articulated in an 1879 US Supreme Court ruling on Baker v. Selden (Simmons 2019).[5]

Inline functions versus external link libraries

This section is to clear up a technical misconception in the earlier email I received.

The simplex code deployment under discussion concerns the use of inline functions copied mostly verbatim from the Numerical Recipes textbook. That earlier email incorrectly describes the NR support present in deeco as being via a proprietary library. Meeker (2025:34) explains the technical distinction between inline functions and external link libraries.

Following from deeco, almost all energy system modeling frameworks these days link dynamically to external optimization solvers, both open source (GLPK and more recently HiGHS) and proprietary (including CPLEX and Gurobi). All OSI‑approved open-source licenses, including the GPLv2, permit this runtime architecture. If Numerical Recipes had indeed provided a link library and not exemplary source code, this post would only have needed to be a couple sentences long in the case of deeco.

License compliance versus copyright infringement

License compliance assessments and copyright infringement actions are different concepts with different objectives and processes. But both rely on the same underlying intellectual property law.

The reuse of source code made public under an approved open source license in your own project is generally seen as a good strategy. That license will offer you a measure of legal certainty but provides no absolute guarantees of legal legitimacy. Indeed, the receiving developer is often reliant on the honesty and diligence of the upstream development teams.

Formalized license compliance is the difficult process of working through your source code dependency graph in a measured and reasoned manner (Wintersgill et al 2024, Meeker 2025).

These legal compliance processes have also been spurred along by new product liability legislation, such as the 2024 EU Cyber Resilience Act.

Meeker (2025) offers a two‑stage approach to license compliance. First, Meeker provides a detailed legal analysis in which she acknowledges that there are many unresolved legal issues “not likely to be cleared up anytime soon”. And then a more pragmatic approach she describes as “legal realism”, framed in terms of the risk of litigation. I am ignoring legal realism here, although the chances of OUP suing the deeco developers in the event of demonstrable copyright infringement is vanishingly small.

Copyright infringement is essentially a civil law matter. And although copyright infringement can technically be a federal crime in the United States, the FBI has not the remotest interest in enforcement.

Only a court of law can definitively determine if a copyright exists in a particular work, whether a defendant did indeed infringe that copyright, that no suitable public interest defenses or legislative exceptions are available or alternatively have been successfully argued, and which limited range of remedies and penalties might be appropriate and required. And as indicated, much of the onus of proof rests with the litigant bringing the action. In the first instance, third parties have no legal standing in proceedings.

Copyright thresholds

Only works that meet certain criteria enjoy copyright projection. Moreover these criteria are subject to somewhat vague minimum requirements that are mostly determined by historical legal precedent. Articulating these thresholds for copyright is generally difficult and also varies by legal jurisdiction and subject matter.

The US Copyright Office (2021:1), current at the time of writing, describes the threshold for copyright in general as follows:

to be copyrightable, a work must qualify as an original work of authorship, meaning that it must have been created independently and contain a sufficient amount of creativity

The bar for software copyright eligibility is widely acknowledged to be low but not zero (SFLC 2007:1). Moreover, originality and creativity are two of the keys, as USCO (2021) above indicates.

Thus, if a particular way of implementing some functionality or solving a problem is widely used and accepted within the software development community, it is unlikely to be considered sufficiently original for copyright to apply.

More generally, the United Stated Copyright Office has often declined to register a copyright — this being a necessary precursor to civil litigation. And from there, there are many cases in which US courts have rejected claims of copyright. Widely cited examples include phone books and yoga postures. And in Europe, photographic snapshots, paintings based on pictures taken by others, and the outlines of scientific papers. In short, the lay public can all too easily overestimate the extent of copyright protection.

Software infringement tests

In terms of legal history, it was not until 1980 that the United States Copyright Act was amended to include computer programs. The 1978 CONTU report suggested and Computer Assocs v. Altai found in 1992 that:[6]

“computer programs, to the extent that they embody an author’s original creation, are proper subject matter of copyright”

United States courts have occasionally developed semi‑formal tests to help examine code similarity in relation to alleged software infringements in cases of non‑literal copying (Lemley 1995:12–17). Literal copying is, of course, straightforward to determine. These tests periodically get replaced as new and different legal facts arise.[7]

I do not need to refer to such tests for deeco because there is no dispute that the source code in deeco is close‑to-identical to the source code published in Numerical Recipes, save for one bug fix. Such legal tests might apply when analyzing the transfers from Künzi et al (1971) to the Numerical Recipes series, for example, when seeking to understand the relative creative contribution from the authors of the Numerical Recipes.

No minimum amount of content

The amount of code copied or adapted is not a consideration under law, because “no objective minimum amount of content is required for a work to be included within the scope of copyright” (SFLC 2007:1).

Some facts regarding deeco

deeco contains 180 or so short lines of C code copied from Numerical Recipes and implemented as an inline function with supporting routines.

The Numerical Recipes suite were certainly written to be used in this way and were regularly used for this purpose. Moreover (as noted earlier) Thomas Bruckner was in contact with the chapter authors about the simplex code and submitted a patch to fix a corner‑case bug. See GitHub for the file containing the modified code:

As an aside, there were no explicit open source solvers when deeco was conceived and written. The GLPK solver was not released until 2000. The GNU Scientific Library (GSL), begun in 1996, does not include linear programming support. The COIN‑OR project was launched as a website in 2000 but it was some time before mathematical programming solvers were offered. The next major open‑source solver project was the HiGHS solver made public in 2021.

Scientific context

This section looks at the scientific context for Numerical Recipes in C textbook in relation to the Simplex method. This context is important for two reasons. Numerical algorithms rarely come from thin air but often have substantial histories of academic and commercial research that includes stepwise improvements and incremental refinements. That progress is often documented in the scientific record and sometimes transmitted to students via teaching and coursework. Both are true in the case of the Simplex method and the Numerical Recipes series. Moreover this churn of development and application is important for both quality assurance and innovation.

The two prefaces for Press et al (1992) indicate that their book is intended for use in higher education.

The simplex algorithm is described as “a popular algorithm for linear programming” on Wikipedia. The original description of the method is contained in George Dantzig (1963) — with 13 675 citations recorded by Google Scholar.

The simplex method has been implemented many times in several programming languages and published in any number of textbooks covering operations research methods.

Indeed, many numerical analysts published example code in instructional books in the early days of computing and it seems unlikely that any of these authors intended that copyright would limit the use of their examples. One legal practitioner suggested to me that one could easily impute implied licensing (given that copyrights are indeed present).

As an aside, a longstanding dilemma in copyright theory is the role that copyright protection plays in “enabling the ongoing progress of knowledge” or otherwise (Samuelson 2016b:33–36). Setting aside enforceability, the restrictions imposed by OUP seem to be unlikely to provide a net benefit to society.

Be aware that some writers, for instance Hornbeck (2020:3), play it safe and recommend that Numerical Recipes code not be used in open source projects. For current projects, that is reasonable advice.

Specific similarities with earlier work

Turning to the Numerical Recipes treatment of Simplex specifically, the chapter authors make reference to numerous researchers in the field and their divergent terminologies. The authors cite Bland (1981) as providing a short semi‑popular survey of the field.

Press et al state that their code in NR is based on Künzi et al (1971) — a textbook with 174 citations according to Google Scholar — as follows:

based algorithmically on the implementation [of Künzi et al (1971)]

There is no specific assertion by the authors of Künzi et al (1968, 1971) that their exemplar source code is protected under copyright, nor does their publisher offer to sell restricted licenses. Nor could it be, given that software copyright only entered into United States law in 1980.

I own the 1968 edition of Künzi et al, while Press et al (1992) refer to the 1971 edition. I am guessing that there is little practical difference in the two texts for the purposes here.

Fig 2: Cover of Künzi et al (1968), published before source code was eligible for copyright

The first question to ask is whether the simplex code in Numerical Recipes is too close to Künzi et al (1971) to warrant a new copyright arising from any changes and improvements that Press et al may have made. My copy of Künzi et al is the 1968 edition, that book being a translation from Künzi et al (1966) written in German.

Künzi et al (1966) was published just three years after Dantzig (1963) released his breakthrough report. Künzi et al (1968:154–161) list 86 packages (or computer codes as they were then known) for linear programming routines in an appendix. Many were developed by engineering corporations and would have been circulated on punched media or as printouts.

Returning to the question: does the act of taking three pages of working ALGOL code and transferring that material to C code create at least some additional copyright? The Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC 2007:1) says:

A program is also unoriginal to the extent that its expression (but not ideas or functionality) is taken from public domain or other existing code.

The programming languages ALGOL and C have much in common. Both are imperative, procedural languages, and the syntax and structure of C was strongly influenced by ALGOL. (My first course in numerical methods was taught using ALGOL 68 and we wrote our assignments on punch cards and ran them on a Burroughs B6700 mainframe.)

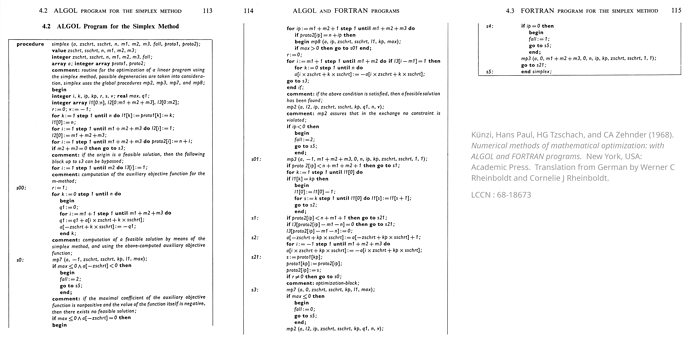

Fig 3: Simplex algorithm in the ALGOL language from Künzi et al (1968:113–115). This is working code.

I undertook a side‑by-side analysis myself. The C code (Press et al 1992:439–441) has been refactored to transfer the coded loops to standalone functions relative to the ALGOL code (Künzi et al 1968:113–115). The variable names and the primary function interface remain similar but not identical. Without stepping through the code by hand, that is all I can reliably say.

Discussions on the internet suggests the implementation of Brents algorithm in Numerical Recipes is also close to an acknowledged earlier publication on which it drew. I myself did not check the details but these hearsay reports seem credible.

On originality and creativity

Following on from an analysis of similarity, literal or otherwise, from earlier works, originality and creativity become the key issues. These come into play here, should it be determined that Press et al do potentially hold at least some copyrightable material in their published Simplex source code.

Any translated code can constitute a derivative work — in our case potentially derivative from Künzi et al (1971). But the code in Künzi et al is not protected due to timing. If Künzi et al had been published after 1980, Press et al could possibly need permission from Academic Press to publish (Bainbridge 1991).

Fair use arguments are often deployed these days and specifically the transformative use doctrine could potentially be claimed as far as original publication is concerned (Russell 2023). Fair use is an affirmative defense, meaning that the defendant must establish their use claims to the satisfaction of the court.

Let us assume, at this juncture, that Press et al do potentially hold partial or complete copyright, have undertaken all due diligence, and have concluded all necessary licensing and/or transfer of copyright arrangements, whether publicly documented or not.

Some of the uptake and usage statistics quoted earlier, including citation counts and software inventories, plus the evidently rapid propagation of research results, lend credence to the view that the Simplex method and its variants were widely known and shared among numerical analysts at that time.

In that context therefore, the mathematical descriptions, pseudocode, and working implementations of the Simplex method can be considered commonplace. Moreover, Press et al freely acknowledge their reliance on such material to guide their expression in software.

The next consideration relies on arguments regarding limits on creativity. And this is the crux issue in my view. Was there is sufficient expression space to warrant copyright — in other words, was the implementation of the Simplex algorithm largely a foregone conclusion?

The Software Freedom Law Center (SFLC 2007:1) says:

If code embodies the only way (or one of very few ways) to express its underlying functionality, that code will be considered unoriginal because the expression is inseparable from the functionality.

According to Malson (2019), the merger doctrine effectively denies the legal originality of some particular expression of an idea, as follows:

The doctrine of merger applies when an idea, by its nature, dictates the form of the idea’s expression. Because the idea so limits the creativity of its expression, the idea and expression are said to “merge”, and be ineligible for protection under copyright.

Regarding computer programs, Malson goes on to discuss whether the plaintiff (injured party) or the defendant (infringing party) should bear the burden of demonstrating whether the expression space is restricted or ample. For complex software, the associated legal investigation can be costly. In a sense, the deeco project might be viewed as a hypothetical defendant trying to prove that the implementation of the Simplex method is almost entirely proscribed by the formal description of the Simplex algorithm.

Samuelson (2016a:40), in a similar vein, opines that function (under its general meaning) and expression can merge, including for software:

Copyright law has long recognized that when there is only one or a small number of ways to express an idea or function, copyright protection will be withheld to any expression that has merged with the idea or function.

Samuelson (2016b:11) expands on the merger doctrine and the role that substandard alternatives may play:

Courts in numerous merger cases have taken into account whether the alternative expressions were inferior in some way, such as because they were less efficient, impractical, unreasonable, illogical, or contrary to industry expectations. Courts have been wary of forcing later authors to adopt inferior expressions or to engage in needless variations.

Algorithmic efficiency is therefore a key consideration when determining whether the expression of a computer routine should be afforded copyright protection or not.[6:1] And, as numerical analysts will know, solver performance is highly sought after and widely studied.

But the legal issues may run deeper. Samuelson (2016b:33–36) argues that the merger doctrine is being used by judges in certain circumstances to avoid confronting the scope of copyright rules contained in the US Copyright Act itself and specifically §102(b).[8] Indeed, US courts, when adjudicating cases involving the “building blocks of knowledge”, Samuelson opines, will apply the merger doctrine to exclude copyright protection, in preference to invoking arguments arising from §102(b).[9]

I contend that wide‑purpose numerical algorithms, including the Simplex method, would fall under this building blocks rubric. This then could make it even less likely that a US court would rule in favor of applying copyright protection to the Numerical Recipes simplex code.

The merger doctrine is not without controversy. The doctrine can be and is applied across all types of copyrighted material (Loren and Reese 2019). But the discussion here is narrowed to software, of course.

Stepping back, Samuelson (2016b:40–47) further indicates that there is a growing reluctance by US courts generally to place the building blocks of knowledge under copyright protection on a range of public benefit grounds: promotion of completion, promotion of access to information, promotion of freedom of expression, recognition of legislative constraints, avoidance of needless variation, and the enabling of efficiency and standardization. And that the merger doctrine is increasingly being used as the main vehicle for dismissing claims of infringement in these circumstances.

For completeness, computer programs in the United States may also be protected as trade secrets and through the grant of software patents (Lemley 1995). Neither mechanism applies here.

Recent commentaries

The following passage was written on 30 May 2025 under CHR rules in relation to another matter, but I think it is quite relevant and succinct here (Americanisms altered):

[Establishing copyright infringement in relation to] software is particularly difficult because of its functional nature. At least in the US, copyright does not extend to works that are similar because they are solving the same problem in the most efficient way, or are common solutions used by many, such as taught in universities, or driven by externalities such as hardware or APIs.

And I received the following remark as personal correspondence in October 2025:

But all of this illustrates that copyright is a very awkward body of law to protect software. The value of code is function, not expression, and function is precisely what the law does not protect.

My analysis

Without commissioning a legal opinion on this matter, it is inconceivable to me that the 180 lines of simplex code in deeco could be anything but public domain under United States law.

With the merger doctrine applied, the earlier question of whether the simplex code from Press et al (1992) is either entirely original or derivative on Künzi et al (1966, 1968, 1971) then becomes academic.

European Union law

As an aside, European law in this context differs somewhat from United States law. For background, FSFE (2025) is recommended:

We now know that the EU standard requires the making of ‘free and creative choices’ and that the work carries the ‘personal touch’ of its author.

Some further observations

It disturbs me that a university publishing house is still claiming copyright today where almost certainly none exists and then offering their code (noting that some source code is marked pubic domain) under a highly restrictive software licensing regime. That original licensing model remains in place at the time of writing with a price tag of USD $95.00 for limited use and distribution rights.

If you reject the public domain arguments in this post, then it becomes somewhat incongruous that the Numerical Recipes suite often drew on prior implementations of algorithms that predated software copyright and then claimed the resulting intellectual property. These facts could well make litigation difficult for OUP because any claim to ownership by OUP might fail to meet the threshold that their creative additionality was substantive.

Some of the lead‑up work for the Numerical Recipes series was supported by the US National Science Foundation. Science funders would be well advised to require the licensing of research outputs in support open science. At that can be said for Numerical Recipes in this context is that it spawned a raft of equivalent open source projects.

I do not recommend using Google queries or other AI assistance to determine legal questions without tracking back to primary sources and reviewing them carefully. The results may be highly spurious otherwise (Booth 2025).

The term “IP maximalism” refers to a doctrine that seeks to place all intellectual and artistic outputs under some form of intellectual property protection, advocates strong limits exceptional use, and prefers market transactions to control and drive usage and generation. Some notable legal scholars view this doctrine as socially counterproductive and I would agree.

My conclusions

Any matters raised concerning copyright scope, copyright thresholds, and software license compliance should be treated using the norms broadly adopted by the open source movement and under the burdens of proof that would arise within civil litigation.

I have argued — convincingly I hope — that the deeco codebase with its copied source from Numerical Recipes does indeed class as genuinely open‑source in legal terms.

My key argument is the application of the merger doctrine, now a central pillar under US copyright law. The Simplex method source code from Numerical Recipe should be considered public domain.

To posit that some hypothetical court would rule adversely on copyright infringement in the case of the NR simplex code represents, in my view, a legal fiction and falls well outside the norms of both open source development and academic engagement. This would also paradoxically constitute an argument against open science.

Lay people often mistakenly see copyrights where none exists, particularly where doing so would strengthen their desired positions.

I would willing concede if I thought that the deeco codebase was legally encumbered. However, to the best of my understanding and analysis, that is not the case.

It should also be recognized that the ethics and practices of collaborative software development evolved substantially over the five or so years of public development for deeco spanning 2001–2006. And looking back over those times should be tempered with some humility. Indeed just reflect on how our current legal practices might be viewed in hindsight from the year 2050.

References

Bainbridge, David I (1991). “The scope of copyright protection for computer programs”. The Modern Law Review. 54: 643–. ISSN 0026-7961.

Booth, Robert (6 June 2025). “High court tells UK lawyers to stop misuse of AI after fake case-law citations”. The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077.

CONTU (31 July 1978). Final report of the National Commission on New Technology Uses of Copyrighted Works (CONTU final report). Washington DC, USA: Library of Congress. ISBN 0‑8444‑0312‑1. Stock no: 030‑002‑00143‑8.

Dantzig, George B (August 1963). Linear programming and extensions — R‑366‑PR. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press.

FSFE (15 May 2025). The threshold of originality for copyrightable source code — Legal corner. Free Software Foundation Europe (FSFE). Berlin, Germany.

Hickey, Kevin J (5 October 2021). Google v. Oracle: Supreme Court rules for Google in landmark software copyright case. Washington DC, USA: US Library of Congress Congressional Research Service. Marked Legal Side Bar.

Hornbeck, Haysn (28 January 2020). Fast cubic spline interpolation. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary. Technical report.

Künzi, Hans Paul, HG Tzschach, and CA Zehnder (1971). Numerical methods of mathematical optimization: with ALGOL and FORTRAN programs. New York, USA: Academic Press. Translation from German by Werner C Rheinboldt and Cornelie J Rheinboldt. Corrected and augmented edition. URL is for front matter.

Künzi, Hans Paul, HG Tzschach, and CA Zehnder (1968). Numerical methods of mathematical optimization: with ALGOL and FORTRAN programs. New York, USA: Academic Press. Translation from German by Werner C Rheinboldt and Cornelie J Rheinboldt.

Künzi, Hans Paul, HG Tzschach, and CA Zehnder (1966). Numerische Methoden der mathematischen Optimierung (mit ALGOL und FORTRAN Programmen) [Numerical methods of mathematical optimization (with ALGOL and FORTRAN programs)] (in German). Stuttgart, Germany: BG Teubner Verlag. Original version.

Lemley, Mark A (1995). “Convergence in the law of software copyright?”. High Technology Law Journal. 10 (1): 1–34. ISSN 1086-3818.

Loren, Lydia Pallas and R Anthony Reese (June 2019). “Proving infringement: burdens of proof in copyright infringement litigation”. Lewis and Clark Law Review. 23: 612–. ISSN 1557-6582. Legal studies research paper series no 2019‑51.

Malson, William (18 November 2019). Modifying the Altai test: the copyright doctrines of merger and scenes a faire should be applied differently for computer programs. University of Cincinnati Law Review Blog.

Meeker, Heather (13 January 2025). Open (source) for business: a practical guide to open source software licensing (4th ed). South Carolina, USA: Kindle Direct Publishing Platform. ISBN 979-830579405-2. Paperback edition. (Ask me if you need a legitimate PDF).

Press, William H, Brian P Flannery, Saul A Teukolsky, and William T Vetterling (30 October 1992). Numerical recipes in C: the art of scientific computing (2nd ed). United Kingdom, USA, Australia: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. ISBN 978-052143108-8. Printed in the USA. Most code is claimed copyright of the publisher, the remainder being public domain.

Raymond, Eric S (2001). The cathedral and the bazaar: musings on Linux and open source by an accidental revolutionary. Sebastopol, California, USA: O’Reilly Media. ISBN 978‑0‑596‑00108‑7. Extended version of his essay originally published in 1999.

Russell, Zachary Dean (24 March 2023). Should we take a closer look at the copyright implications of translating computer code?. Preprint?

Samuelson, Pamela (2016a). “Functionality and expression in computer programs: refining the tests for software copyright infringement”. Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 31: 1215–. ISSN 1086-3818. Given URL is for a post‑print.

Samuelson, Pamela (2016b). “Reconceptualizing copyright’s merger doctrine”. Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA. 63: 417–. ISSN 0886-3520. Given URL is for a post‑print.

SFLC (27 September 2007). Originality requirements under US and EU copyright law. New York, USA: Software Freedom Law Center. Creative Commons CC‑BY‑SA‑3.0 license. ![]()

Simmons, Joshua L (2019). “The five W’s of merger”. Columbia Journal of Law and the Arts. 43: 407–. ISSN 1544-4848.

US Copyright Office (ongoing). Copyright Law of the United States. US Copyright Office. Washington DC, USA. Web version.

US Copyright Office (March 2021). Works not protected by copyright — Circular 33. Washington DC, USA: United States Copyright Office.

Wintersgill, Nathan, Trevor Stalnaker, Laura A Heymann, Oscar Chaparro, and Denys Poshyvanyk (12 July 2024). ““The law doesn’t work like a computer”: exploring software licensing issues faced by legal practitioners”. Proceedings of the ACM on Software Engineering. 1 (FSE): 882–905. Article 40. ISSN 1049-331X. doi:10.1145/3643766. Reference: ACM 2994-970X/2024/7-ART40. Creative Commons CC‑BY‑4.0 license. ![]()

▢

L. McHardy v. Various Parties. (Meeker 2025:238–285). Geniatech v. McHardy Wikipedia. ↩︎

Software Freedom Conservancy v. Vizio, Superior Court of California, County of Orange, 10/19/2021, 30-2021-01226723-CU-BC-CJC. ↩︎

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp. 545 F. Supp. 812, 823 (E.D. Pa. 1982), rev’d, 714 F.2d 1240, 1253 (3d Cir. 1983). ↩︎

Baker v. Selden, 101 U.S. 99 (1879) US Supreme Court. Wikipedia. ↩︎

Computer Assocs Int’l v. Altai, Inc, 982 F.2d 693 (2d Cir. 1992). ↩︎ ↩︎

In terms of United States law, two such tests are SSO and AFC (Samuelson 2016a). ↩︎

US Copyright Act §102(b) : In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work. ↩︎

The first case to use such language was: CCC Information Services v. MacLean Hunter Market Reports. 44 F.3d 61, 68-70 (2d Cir. 1994). ↩︎