Release 04 04 Nov 2025 WorkingDoc

TL:DR

This post provides a social history of the deeco (dynamic energy, emissions, and cost optimization) codebase and project. The codebase is now archived on GitHub.

One reason for offering this historical material is that there is now interest within the modeling community to document the early days of modeling software development. This blog can contribute to those endeavors.

This post is written to the best of my knowledge. If you notice any errors or omissions, please contact me via PM or email or reply below.

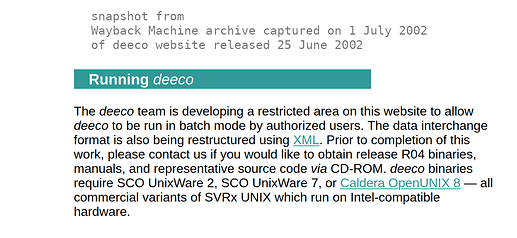

The GNU GPLv2 license was added to the deeco codebase in 2000 and efforts were well underway the following year to distribute the binaries and source code, to provide remote execution and development environments, and to build user and developer communities. deeco executables would only compile and run on a subset of UNIX operating systems, which then led to some of the rather unusual solutions described here.

Thus 2001 represents the year that the deeco project became a fully‑fledged open‑source project in both legal and social terms.[1]

Keep in mind that open source was a novel and largely untested concept during these times and there was absolutely no case law on FOSS licensing at that time. It would not be until 2010 that a US court even considered the legitimacy of open‑source public licensing, fortunately returning an affirmative view.[2]

An allied post has addressed the legal question of whether the source code for deeco was tainted by the addition of Simplex method code copied almost verbatim from a Numerical Recipes textbook. My conclusion — supported by academic literature, official descriptions, and guidance from the FSFE legal community — is that the simplex code in question is not protected by United States copyright law and that this near‑literal transfer of 180 short lines of C language code from Numerical Recipes does not invalidate the open‑source status of deeco.

deeco also presented a very different modeling paradigm from the then established mathematical programming approach. deeco was implemented using an object-oriented language and first completed in 1995.

deeco also utilized high‑resolution contiguous‑time time horizons whereas the other frameworks from that era employed typical summer and winter time‑slices. Use of contiguous (unbroken) time enabled deeco to better represent renewable generation and long‑haul storage relative to its contemporaries.

Introduction

The post was written after I received an email in late‑May 2025 that contained a number incorrect assumptions about the technical, legal, and social status of deeco. Rather than address those inaccuracies directly, this post instead provides a more representative and complete history.

That email also claimed that the use of proprietary programming libraries would — and this is separate from the near‑literal copying of C code from Numerical Recipes — invalidate the open‑source status of deeco. However, such usage is expressly permitted by the GPLv2 license. More on this later.

If deeco is indeed properly licensed and my descriptions of the attempts to build a wider community are accurate, then deeco represents the first proactive open‑source energy system modeling project by a very significant margin.

deeco is a high‑resolution contiguous‑time energy system modeling framework written in C++ and completed in 1995. Helmuth Groscurth developed the model architecture (Groscurth et al 1995) and Thomas Bruckner, then at the Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Würzburg, Germany, designed and implemented the software over three years (Bruckner 1997a).

My involvement began when I emailed the authors of deeco in circa 1995 and requested their source code, having stumbled across Groscurth et al (1995). I was then a masters student in the Physics Department, Otago University, New Zealand. I was forwarded the source code and ported deeco from a Hewlett-Packard UNIX workstation to a PC computer in 1998 and proposed a national policy model for New Zealand (Morrison 2000).

deeco was originally intended for municipal energy systems embedded within national or transnational energy systems. Deploying the deeco framework to an albeit largely islanded national energy system was a novel application for the project.

Later, while studying at the Institute for Energy Engineering (IET), Technical University of Berlin, I persuaded Dr Bruckner to license deeco under a GPLv2 license. The Institute then purchased an Intel desktop computer named helgoland to function as a remote SSH secure shell server. I maintained that server and also wrote and maintained a project website. deeco was distributed first via CD‑ROM and later by SSH download. More history later.

Fig 1: The helgoland server was assembled to specification on 27 July 2001

The deeco codebase itself was archived on GitHub in 2017 for historical reasons:

The deeco website went live on 3 January 2001 and was occasionally captured by the Internet Archive Wayback Machine from 1 July 2002 until 16 November 2006 (that late start was because the deeco website predated the Wayback Machine):

The Wayback Machine is considered a reliable source of information and the Internet Archive will willingly write affidavits on request for use in civil proceedings.

Fig 2: Screenshot of deeco project website on running the software

The historical setting in important too. Recognition of the role of copyright, open‑source licensing, and the norms of shared community development evolved strongly over the period that deeco was an active project. An allied post provides a timeline.

In regards terminology: “deeco” may refer variously to the deeco codebase, the wider deeco ecosystem, or the deeco project overall. The stub “NR code” is a placeholder for the Simplex method C source code and commentary from Numerical Recipes (Press et al 1992:430–444).

Context

The context in which the deeco project sits is important. In 2000, the concept of open source was in its infancy. Eric Raymond (1999) had just published his widely read Cathedral and Bazaar the previous year. Creative Commons licenses did not exist. License compliance, community enforcement, and direct litigation were in future. It was not until 2010 that it was known that a court of law anywhere in the world would recognize the concept of open‑source public licensing. The Open Source Initiative advocacy organization was just two years old. The SourceForge discovery and hosting site was operating by then but was not widely known. Many open‑source projects still relied instead on a lead maintainer who periodically collated, released, and distributed tarballs by email or FTP server.

It is useful to evaluate the social dimension of the deeco project in the context of its time and not how a similar project might be enacted in 2025. On that latter count, deeco of course performs poorly by today’s technologies and expectations.

Project details

deeco was in active development and use for a period of about 14 years. Seven people contributed directly to the deeco codebase, but admittedly none from outside the wider research group.

Precursor

The precursor to deeco was named ECCO (energy, cost, and carbon dioxide optimization) and coded in Pascal by Helmuth Groscurth (Groscurth et al 1993).

Intel port

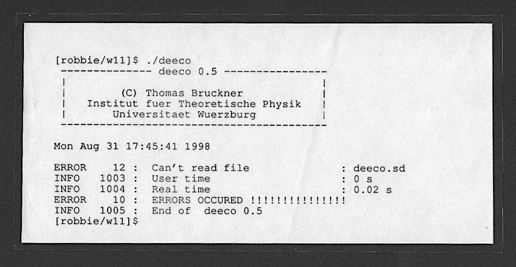

deeco was first developed on a high‑end Hewlett-Packard HP‑UX UNIX workstation. SCO UnixWare ran on cheaper Intel‑compatible hardware and offered the same C++ development environment. Consequently the Physics Department, Otago University purchased desktop hardware named Suzie (after a Calvin and Hobbes character) and a copy of SCO UnixWare 2 and I ported the deeco codebase across during 1998.

Fig 3: deeco splash screen (as printout) from the Intel port

Open sourcing plans

Plans to distribute deeco free‑of‑charge were recorded in the academic literature as quoted below (Lindenberger et al 2000:592). Note the use of the term “freeware” at this juncture, however deeco was released under a GNU GPL license at my prompting (emphasis added).

Thanks to these efforts, especially those of Robbie Morrison, it has been possible to port the deeco software from UNIX workstations to a personal computer environment. Now deeco is a step closer to becoming a freeware planning tool for managers of municipal energy systems during a time when these systems undergo profound changes due to the liberalization of the energy markets and the pressure to reduce CO2 emissions according to the agreements of the Third Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in Kyoto, 1997.

In terms of timing, deeco was fully implemented and well tested when it was made public. Similar project have gone live after two weeks of programming effort. Both strategies are legitimate, of course.

One of the more interesting theoretical results arising from deeco was an evaluation of the effects of counteraction and synergy across different high‑resolution system scenarios (Bruckner et al 1997).

The application of deeco to New Zealand over 1995–2000 represents the first time a high‑resolution contiguous‑time energy system modeling framework had been applied to a national problem to my knowledge (Morrison 2000). That work was never completed but there is only so much distance that a single isolated masters project can cover.

Community building

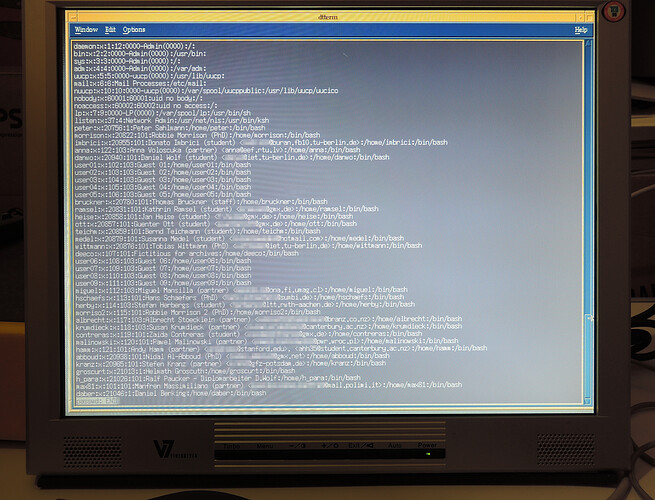

From 2001–2005, I signed up 12 external accounts on the helgoland UNIX server located at the TU Berlin. TU Berlin students and staff (excluding the institute sysop) added another 13 user accounts to helgoland. There were also two further accounts on stand‑alone machines bring the total number of signed‑on deeco users to 27 individuals.

Some users were provided with accounts after finding the deeco website independently and then contacting the project organizers by email.

To my knowledge, none of the external accounts were used for modeling, but equally I might not have known. The deeco source and executables may have also been downloaded and used on local systems but that seems unlikely. For context, Meeker (2025:89–106) discusses at length the awkward concept of software distribution under US copyright law.

Fig 4: UNIX terminal displaying 25 user accounts on helgoland

The user accounts on helgoland included the following affiliations: Building Research Association of New Zealand (New Zealand), GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences (Germany), Polytechnic University of Milan (Italy), Riga Technical University (Latvia), RWTH Aachen University (Germany), Stanford University (USA), Technische Universität Berlin (Germany), University of Canterbury (New Zealand), University of Cologne (Germany), University of Magallanes (Chile), and University of Wrocław (Poland). To which Otago University (New Zealand) can be added for the Intel port on Suzie and University of Würzburg (Germany) for the original development on Hewlett‑Packard hardware.

The SSH development environment was frankly awful. The UNIX system was arcane, SSH access offered only a minimal command shell (80 columns × 24 lines), the command‑line compiler was difficult to use, server‑side editing required the use of vi, and rudimentary version control was limited to CSV.

The fact that the deeco project did not attract much external activity was not through lack of effort. Back then though, energy system modeling was the preserve of international institutions using numerical models with their development roots in the 1970s oil crisis. There was limited academic interest in the domain of energy system analysis. Open‑source software development was still quite rarefied too. Government agencies were generally focused on neoliberal economics and scenario‑based public‑interest systems analysis was viewed as unnecessary at best.

I readily concede that the deeco project failed to garner a working community outside of the core group. That type of success would come a decade or so later with other projects. But deeco does represent a genuine attempt to build such a community over a period of about five years spanning 2001–2006 and those efforts should be acknowledged.

deeco fared better in terms of research use. Looking back, deeco was used on about ten academic projects, including one significant research project funded by the Bavarian Research Foundation (labeled ISOTEG) and a number of honors and masters projects that spanned three universities in Germany and one in New Zealand. The Hamburgische Electricitäts-Werke (HEW) was an industry partner.

Contributors to the deeco codebase comprised Thomas Bruckner, Johannes Bruhn, Jan Heise, Dietmar Lindenberger, Susanna Medel, Robbie Morrison, and Kathrin Ramsel.

The legal and social aspects of open‑source development are separate in the sense that a codebase may be legitimately open‑source with no attempt to build a surrounding community. This was not the plan for deeco.

Publications

My records show that the deeco project resulted in 13 peer‑reviewed publications (with six listed here), 2 conference papers, 3 software manuals, and at least 2 university theses.

Abandonment

The deeco project was abandoned around 2006 after key AT&T programming libraries (described in the next major section) became stranded. These libraries were effectively casualties of the so‑called UNIX wars, in which various UNIX vendors struggled for dominance by creating competing operating system standards. In some sense, the deeco project was collateral damage.

In theory, the deeco codebase could have been reimplemented using the more portable STL library but that didn’t happen. In any event, interpreted languages, like Python and Julia, later gained ascendancy in this domain. In all honesty, stranding aside, it is debatable whether the deeco project would have continued for much longer as compiled software.

Forensics

I have the two mirrored hard‑drives (HDD) from the helgoland server. Unfortunately both use the proprietary UNIX SYSV HTFS (high throughput filesystem) owned by the SCO Group and suitable drivers are no longer available. I have been exploring commercial data recovery options, so far without success.

A proprietary compiler is acceptable

Skip this section if you don’t wish to drill down into the details of the GPLv2 license.

deeco made use of the proprietary system compiler suite bundled with the Hewlett‑Packard HP‑UX operating system and later the SCO UnixWare versions 2 and 7 operating systems. The compiler suite included the AT&T Unix System Laboratories (USL) Standard Components (SC) 3.0 C++ library. The C++ language was designed to be a stripped down language with wider development supported by innovative third‑party libraries, the more useful of which could become formal standards.

It was suggested in that same email mentioned earlier, that use of proprietary programming libraries by an open‑source project would naturally render the resulting codebase and binaries invalid. But such usage is covered under the system library exception of the GPLv2 license and this provision applies equally to deeco (Meeker 2025:49). It does not matter whether the programming library in question is header‑only, statically linked, dynamically linked, or reliant on some other protocol.

Note also that the first wave of GNU software was developed on proprietary tooling — indeed there was no other choice for several years until the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) became usable in production.

My conclusions

I hope I have convincingly shown that deeco was a sophisticated and versatile energy system modeling framework, that its codebase was legitimately open licensed in 2000 — as documented in an allied post — and that its social history shows it was a genuine open‑source project from 2001 until its cessation in 2006. The direct cause of failure was the deprecation of key C++ programming libraries by the SCO Group.

It should also be recognized that the ethics and practices of collaborative software development evolved very substantially over the 14 year development horizon of deeco spanning 1992–2006. And looking back over those times should be tempered with some humility. Indeed, just reflect on how our current open‑source development practices might be viewed in hindsight from the year 2050.

deeco remains, to the best of my knowledge, the first energy system framework to employ object‑oriented programming (OOP) rather than mathematical programming (MP) as its design paradigm (Groscurth et al 1995).

And, to the best of my knowledge, deeco remains the first energy system framework to utilize a high‑resolution contiguous‑time time horizon — now regarded as indispensable for analyzing renewables technologies and legacy and contemporary storage systems (Lindenberger et al 2000).

References

Bruckner, Thomas (2001). Benutzerhandbuch ‘deeco’ — Version 1.0 [User handbook ‘deeco’ — Version 1.0] (in German). Berlin, Germany: Institut für Energietechnik (IET), Technische Universität Berlin. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5148149. 239 pages.

Bruckner, Thomas, Helmuth‑M Groscurth, and Reiner Kümmel (1997). “Competition and synergy between energy technologies in municipal energy systems”. Energy. 22 (10): 1005–1014. ISSN 0360-5442. doi:10.1016/S0360-5442(97)00037-6.

Bruckner, Thomas (1997a). Dynamische Energie- und Emissionsoptimierung regionaler Energiesysteme — PhD thesis [Dynamic energy and emissions optimization of regional energy systems — PhD thesis] (in German). Würzburg, Germany: Institut für Theoretische Physik, Universität Würzburg.

Bruckner, Thomas (1997b). ‘deeco’ — Programmer’s manual. Würzburg, Germany: Institut für Theoretische Physik der Universität Würzburg.

Bruckner, Thomas (1997c). ‘‘deeco’’ — Benutzerhandbuch. Institut für Theoretische Physik der Universität Würzburg.

Groscurth, Helmuth‑M, Thomas Bruckner, and Reiner Kümmel (1995). “Modeling of energy-services supply systems”. Energy. 20 (9): 941–958. ISSN 0360-5442. doi:10.1016/0360-5442(95)00067-Q.

Groscurth, Helmuth-M, Thomas Bruckner, and Reiner Kümmel (1993). “Energy, cost, and carbon dioxide optimization of disaggregated, regional energy-supply systems”. Energy. 18 (12): 1187–1205. ISSN 0360-5442. doi:10.1016/0360-5442(93)90009-3.

Lindenberger, Dietmar, Thomas Bruckner, Robbie Morrison, Helmuth-M Groscurth, and Reiner Kümmel (2004). “Modernization of local energy systems”. Energy. 29 (2): 245–256. ISSN 0360-5442. doi:10.1016/S0360-5442(03)00063-X.

Lindenberger, Dietmar, Thomas Bruckner, Helmuth-M Groscurth, and Reiner Kümmel (2000). “Optimization of solar district heating systems: seasonal storage, heat pumps, and cogeneration”. Energy. 25 (7): 591–608. doi:10.1016/S0360-5442(99)00082-1. Mentions plans to open‑source.

Meeker, Heather (13 January 2025). Open (source) for business: a practical guide to open source software licensing (4th ed). South Carolina, USA: Kindle Direct Publishing Platform. ISBN 979-830579405-2. Paperback edition. (Ask me if you need a legitimate PDF).

Morrison, Robbie (2 July 2002). Flier describing deeco energy modeling environment — Issue A. Berlin, Germany: Institute for Energy Engineering (IET), Technische Universität Berlin (TU Berlin). doi:10.5281/zenodo.4836069. ![]()

Morrison, Robbie (31 July 2000). Optimizing exergy-services supply networks for sustainability — MSc thesis. Dunedin, New Zealand: Physics Department, Otago University. doi:10.5281/zenodo.13360487. ![]()

Press, William H, Brian P Flannery, Saul A Teukolsky, and William T Vetterling (30 October 1992). Numerical recipes in C: the art of scientific computing (2nd ed). United Kingdom, USA, Australia: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. ISBN 978-052143108-8. Printed in the USA. Most code is claimed copyright of the publisher, the remainder being public domain.

Raymond, Eric S (2001). The cathedral and the bazaar: musings on Linux and open source by an accidental revolutionary. Sebastopol, California, USA: O’Reilly Media. ISBN 978‑0‑596‑00108‑7. Extended version of his essay originally published in 1999.

▢