Release | 03

As of May 2022, the European Union is considering a new data producers right for raw machine‑generated data as part of the proposed Data Act. There is currently no carve out for information of public interest. I am personally terrified that most of the officially published information that is needed for high‑resolution energy system analysis will be legally encumbered and not available for open modeling and open science more generally. Moreover, getting public institutions to use Creative Commons CC‑BY attributions licenses as a way of compensating has proved difficult to date. And in any case, Creative Commons will doubtless need to issue a revised CC‑BY‑5.0 license to cover this new property right too. This posting scopes the issues. While keeping in mind that where legal uncertainty exists, researchers invariably err on caution.

Disclaimer: the author has no legal training and the material presented should be interpreted within that caveat.

Context

Access to robustly reusable data of public interest is becoming increasingly problematic in Europe. That includes the information required to analyze development pathways that honor rapid decarbonization. The Open Data Directive 2019/1024 was a clear step backward in this regard by neutering the legal notion of re‑use (see §2.11) despite its high‑flying ideals (see recital 16) and a misleading title (implying support for “open data”).

The focus of this posting is a novel property right for machine-generated data currently being considered by the European Parliament as part of the proposed Data Act. And as I and others argue, its adoption under its current scoping would be a disaster for transparent and reproducible public interest analysis.

These developments contrast with incremental progress toward open energy data being made in the United Kingdom. And a long‑established tradition of public domain data in the United States, together with intellectual property law that effectively excludes routine data from protection due to insufficient human creativity.

The discussion here is limited to non‑personal information.

Proposed novel property right for machine-generated data

The proposed Data Act, currently before the European Parliament, contains provisions to create a novel European property right for raw machine‑generated data. This new right is similar in intent to 96/9/EC database protection but without requiring that substantial investment, substantial extraction, and human agency be present. Notwithstanding, the legislative wording remains sketchy at this juncture.

Advocacy group Open Future provides an excellent critique of this proposal and documents the underlying motives as well:

- Tarkowski, Alek and Francesco Vogelezang (10 December 2021). The argument against property rights in data — Policy brief #1. Europe: Open Future. Creative Commons CC‑BY‑4.0 license.

Although the publication of Tarkowski and Vogelezang (2021) predates the latest official release of the proposed Data Act on 23 February 2022, their arguments stand nonetheless (I presume the authors relied on the well‑publicized leaked draft via Bertuzzi 2022). The proposed Data Act, in its current official form, can be found as follows (and search on “machine-generated” for the points under discussion):

- European Commission (23 February 2022). Data Act: Proposal for a Regulation on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (text with EEA significance) — COM(2022) 68 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

Felix Reda (previously Julia), a former Member of the European Parliament (MEP), warned five years ago that this novel instrument was being justified on much the same faulty logic that underpinned the 96/9/EC database rights that entered into European Union law in 1996 (with transposition into member state national law following on):

- Reda, Julia (2017). Learning from past mistakes: similarities in the European Commission’s justifications of the sui generis database right and the data producers’ right. In Sebastian Lohsse, Reiner Schulze, and Dirk Staudenmayer (editors). Trading data in the digital economy: legal concepts and tools. Pages 295–304. Baden‑Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlag. ISBN 978‑1‑5099‑2120‑1.

Tarkowski and Vogelezang (2021:7–8) specifically highlight the dangers posed to science:

[T]he new right would strongly affect freedom of expression and information as well as freedom of scientific research and services, given that it would greatly reduce overall information availability. In this light, the European legislator would have to prove that a new property right would be socially and economically justifiable for information access by citizens and researchers.

And that generating data is increasingly a joint undertaking rather than an individual activity (p8):

[D]ata is increasingly seen as relational and co-generated. Salomé Viljoen (2021) proposes that the relational character of data means that for any exchange of data there are collective–even population-level–interests that cannot be reduced to individual interests. A related argument is made by the GPAI [Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence] Data Governance Working Group, which recognizes that data is increasingly generated collectively by several different entities. These characteristics of data imply competing interests among various actors in the data economy. Exclusive property rights can therefore easily be questioned by other parties, asking for recognition of their rights in data.

The scope of this proposed instrument would surely include the outputs from energy system models. The good news is, I guess, that modelers can waive such rights by attaching Creative Commons CC‑BY attribution licenses (or a CC0‑1.0 waiver or something else inbound compatible to CC‑BY).

But this novel instrument would also give those supplying information under statutory reporting new and solid intellectual property (IP) rights. And that would include the transmission system operators who contribute grid status information to the ENTSO-E Transparency Platform and the EEX electricity market operator who makes public market clearance information. At present, there is no real basis for IP to attach to this kind of data. And indeed some in this energy modeling community treat information sourced from the ENTSO‑E Transparency Platform as legally unencumbered. But that practice could not continue with this new provision without the prospect of actionable property rights infringement.

Looking along the data processing pipeline, there is no legal consensus on how and under what circumstances rights attached to input data can transmit to output data. The legal question is whether the resulting output constitutes a new work or a derivative work. Most of the admittedly limited analysis on this question focuses on machine learning and big data, but more conventional numerics (such as that found in energy system models) should not be much different in this regard in legal terms. Even if a new work was indeed created, researchers cannot, by default, republish their input data to facilitate open science and analytical transparency.

In summary, this proposed novel property right for machine-generated data provides a real threat to public interest analysis because such analysis will invariably draw on encumbered or potentially encumbered information. And that would, under current circumstances, include the statutory reporting of information on grid status and market clearance.

Community submissions

For completeness, there were two submissions on the proposed Data Act from this community — although the issue of machine‑generated data was not traversed in either:

-

Morrison, Robbie (25 June 2021). Submission on a proposed Data Act for the European Union from the perspective of energy system analysis — Release 07. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5032198. Berlin, Germany. Creative Commons CC‑BY‑4.0 license. 16 submitters.

-

Morrison, Robbie (3 September 2021). Submission on a proposed Data Act for the European Union from the perspective of energy system analysis / 2 — Release 02. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5471077. Berlin, Germany. Creative Commons CC‑BY‑4.0 license. Sole submitter.

My thoughts

Stepping back, my general reaction on these current legislative reforms that fall under the rubric of the EU Digital Single Market are as follows. With this first point being the most important:

- there needs to be a much sharper distinction between published information of public interest and other classes of information — moreover, public interest information must be made explicitly and genuinely usable and reusable

And continuing:

- there needs to be a greater recognition that data sharing and open data are markedly different concepts with very different underlying rationales, objectives, and use‑cases

- the proposed new intellectual property right for machine-generated data (as discussed here) should be shelved

- the existing 96/9/EC database right should be abandoned completely — or failing that, be subject to examination, registration, and annual fees (like trademarks and patents) and also expressly excluded from all material under statutory reporting (not currently the case)

- definition §2.11 for “re‑use” in the misleadingly‑named Open Data Directive 2019/1024 should be reworked to align with majority perceptions on that concept

- proactive legislative support for an information commons should be considered — indeed there are no provisions in law in Europe or elsewhere (that I am aware of) that fill the legislative void that open content, data, and software licenses have been designed to address

And also:

- the European Commission should add Creative Commons CC‑BY licenses to all material of public interest that it publishes

I wholeheartedly commend Tarkowski and Vogelezang (2021) to anybody wishing to understand the drivers that lie behind the current suite of data reforms by the European Commission. Those drivers clearly prioritize data commodification and the development of a European‑wide data market over an information commons and the public interest usage and re‑usage of socially important information. Moreover I predict that the current policy trajectory will provide no end of headaches for open energy system modelers.

On the upside, France is advocating for a digital commons as part of its EU presidency. This is clearly counter to the direction the European Commission is currently pursuing. More here:

- French Embassy (7 February 2022). France calls for a European initiative for digital commons. France in the UK. London, United Kingdom.

The core question is how far the French government want to push this concept? Or is their initiative destined to remain primarily window dressing?

Further analysis

This section provides a deeper dive into the proposed right and related issues. Feel free to skip to the closure otherwise.

In addition to the proposed Data Act, this section also folds in limitations that derive from the Open Data Directive 2019/1024.

Automatic property rights and legal uncertainty

There are two kinds of intellectual property rights. Copyright, 96/9/EC database protection, and the proposed data producers right attach automatically. And it is thus difficult for a user to know whether the attributes and thresholds for protection have been met and that these various property rights are indeed present or not. Trademarks and patents, in contrast, are subject to application, examination, and determination by disinterested bodies, followed by registration and public record. We are working here therefore with automatic rights and their very nature invites legal uncertainty and particularly in the context of numerical information.

Technical definitions underpinning the proposed data producers right

Technical details are provided in European Commission (2017:9–10), while noting that these details may have been subsequently modified during legislative development:

- “Machine-generated data is created without the direct intervention of a human by computer processes, applications or services, or by sensors processing information received from equipment, software or machinery, whether virtual or real.”

- “Machine-generated data can be personal or non-personal in nature. Where machine-generated data allows the identification of a natural person, it qualifies as personal data with the consequence that all the rules on personal data apply until such data has been fully anonymised (e.g. location data of mobile applications).”

- “Raw machine-generated data are not protected by existing intellectual property rights since they are deemed not to be the result of an intellectual effort and/or have any degree of originality.”

It should be noted that automatically generated data is often screened, corrected, and/or further manipulated by humans prior to publication, using both hand edits and computer scripting. But irrespective of the methods deployed, human judgments are nonetheless applied.

Copyright verbs “use” and “re‑use”

This subsection deals with extant law contained in the Open Data Directive 2019/1024. As indicated, this existing legislation is also highly problematic.

First a note on spelling: the Commission seems to have settled on “re‑use” with a hyphen in its more recent documents. This note treats both spellings of “reuse” and “re‑use” as equivalent.

Under intellectual property law, a so‑called copyright verb describes what a recipient can and cannot do with the work in question in the context of the protection afforded by copyright and related rights. The wider approach is known as grammatical and textual analysis. Such verbs include (taken from provisions in established open licenses): copy, distribute, extract, modify, prepare derivative works, publish, redistribute, reuse, share, and share adapted material (Smith no date, for some examples). But the term “re‑use” does not appear to have a legal definition (the ODD notwithstanding), at least not in the law dictionaries I was able to consult.

Higgs and Gutsche (2021:16) stress the importance of choosing the correct copyright verbs in relation to one’s intended license grant. That exact same sentiment applies to legislation too.

The Open Data Directive 2019/1024 perversely defines “re‑use” as “use” in §2.11. European Commission (2011:40) also earlier defined “reuse” as “use” in §3.2.

It is contended here that this remapped definition to mere “use” has a well established meaning under copyright law and that this meaning would not extend to the right to redistribute in original or modified form. This therefore represents a major impediment to public interest analysis that necessarily seeks to utilize public sector information from within Europe.

Provisions for science versus public interest

There are a number of provisions in European policy and member state statues to provide exceptions for scientific research and education. For instance, in Germany, there are permitted uses for teaching in educational establishments and for non‑commercial scientific research, including provisions specific to personal scientific research. But that scope is not sufficient to enable public interest analysis and democratic debate more generally. Indeed, it is not clear that this particular note would meet the legal classification for research under German copyright law.

Fuzzy boundary between data and code

Another emerging question is to what degree do scripts to download and filter data using remote APIs and/or local processing class legally as data or collections of data or as software? This applies irrespective of whether expressly actioned by users or transacted by data portals or data cataloging services on behalf of end users. And what are the legal implications? Academic analysis on computer‑aided manufacturing files might be applicable in this regard as these fit part‑way between data and code (Osborn 2017).

European Commission JRC identifies a “commons‑based economy”

The Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission has identified a “commons‑based economy” as an important emerging trend (Warnke et al 2019:259). This in clear contrast to the direction of travel indicated by the data producers right.

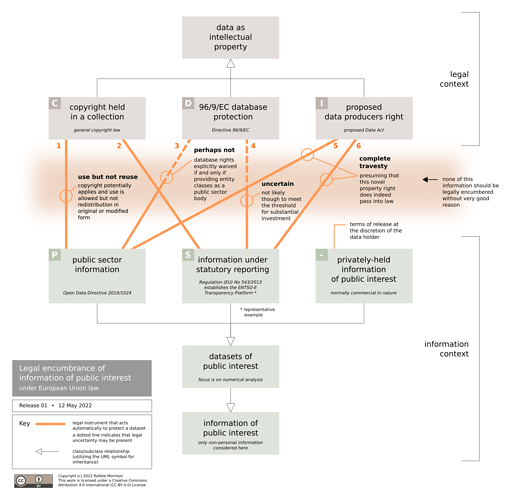

Summary diagram

The following diagram summarizes much the foregoing discussion.

Diagram 1: Legal encumberance of information of public interest under European Union law.

With regard to diagram 1 more specifically. A public sector body is defined in relation to its procurement status and this information is not generally available (line marked 3). 96/6/EC database protection is unlikely to apply to information under statutory reporting as a result of recent litigation (CJEU 2021, Husovec and Derclaye 2021) (line marked 4). The ENTSO‑E Transparency Platform legislation cited is simply illustrative (entity marked S). Information under statutory reporting is sometimes technically encumbered too, no doubt to improve its parallel saleability.

Legal uncertainty is effectively as debilitating as clear but restricted rights. Such uncertainty is indicated through the use of dotted lines on the diagram. And there seems to be little to no legislative appetite to remove or reduce this uncertainty in the context of open data.

New Creative Commons CC‑BY‑5.0 license

I suggest that the Creative Commons CC‑BY‑4.0 license will need to be modified to reflect any novel data producers right that may arise from the proposed Data Act entering into law. And I have provocatively bumped the version number to 5.0 to make the point here that this will doubtless need to be a major revision.

Closure

The Database Directive 96/9/EC, effective in various member states from 1997 onward, introduced the protection of non‑original human‑formed databases within the European Economic Area (EEA) and also the United Kingdom. The protection of machine-generated databases — should the proposal in the Data Act proceed — will again be limited to the EEA. There is no equivalent of either property right in the United States, for example. And the United Kingdom is currently promoting the principle of “presumed open” for energy sector information — which means, I imagine, that Creative Commons CC‑BY‑4.0 licensing or something inbound‑compatible should endure in the absence of personal and commercial privacy considerations. Europe therefore seems well out‑of‑step in this regard.

Re‑use here means the unrestricted right to distribute material in original or modified form albeit often with a requirement to track attribution. This latter aspect is normally not seen as a drawback as this legal metadata also supports information provenance. On that note, metadata should be explicitly licensed using Creative Commons CC0‑1.0 waivers.

I believe the European Commission, Parliament, and Council should be far more cognizant of the importance of published information of public interest and explicitly provide for its free use and re‑use. And therefore abandon this novel proposal for machine‑generated data protection, at least in the important context of public interest information.

If not, the proposed data producers property right will be present or potentially present in almost every slither of numerical information, dataset download, or database inquiry an energy system analyst encounters. Moreover that legal encumbrance will persist and grow along the data processing chain, amplifying legal uncertainty and hindering risk‑averse researchers at every step. I would go as far as to describe this new right a legislatively‑enabled data virus. One that will undermine open research, democratic debate, and public engagement en‑route as it propagates and mixes with unencumbered data. And I can only describe such damage to our public sphere here in Europe as entirely self‑inflicted.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Expansion |

|---|---|

| API | application programming interface |

| CC‑BY | Creative Commons attribution license |

| CJEU | Court of Justice of the European Union |

| EEA | European Economic Area |

| EEX | European Energy Exchange |

| ENTSO‑E | European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre of the European Commission |

| IP | intellectual property |

Statutes

European Commission (23 February 2022). Data Act: Proposal for a Regulation on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (text with EEA significance) — COM(2022) 68 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (26 June 2019). “Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information — PE/28/2019/REV/1”. Official Journal of the European Union. L 172: 56–83.

European Parliament and European Council (27 March 1996). “Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases”. Official Journal of the European Union. L 77: 20–28.

European Commission documents

European Commission (23 February 2022). Commission staff working document on common European data spaces — SWD(2022) 45 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (28 May 2021). Inception impact assessment: Data Act (including the review of the Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases) — Ares(2021)3527151. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission. Lead DG: CNECT/G1. Landing page for download given. Download name: 090166e5ddb6bc31.pdf.

European Commission (25 November 2020). [Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Making the most of the EU’s innovative potential: an intellectual property action plan to support the EU’s recovery and resilience — COM(2020) 760 final](EUR-Lex - 52020DC0760 - EN - EUR-Lex https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0760&from=EN). Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (19 February 2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: a European strategy for data — COM (2020) 66 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (17 May 2019). “Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC”. Official Journal of the European Union. L 130: 92–125.

European Commission Expert Group on FAIR Data (November 2018). Turning FAIR into reality — Final report and action plan from the European Commission Expert Group on FAIR data — KI-06-18-206-EN-N. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978‑92‑79‑96546‑3. doi:10.2777/1524.

Collins, Sandra, Françoise Genova, Natalie Harrower, Simon Hodson, Sarah Jones, Leif Laaksonen, Daniel Mietchen, Rūta Petrauskaité, and Peter Wittenburg (November 2018). Turing FAIR into reality: final report and action plan from the European Commission expert group on FAIR data — KI-06-18-206-EN-N. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978‑92‑79‑96546‑3. doi:10.2777/1524. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation.

European Commission (25 April 2018). Commission staff working document — Impact assessment — Accompanying the document: Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the re-use of public sector information — SWD (2018) 127 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (25 April 2018). Commission staff working document — Evaluation — Accompanying the document: Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the re-use of public sector information — SWD (2018) 145 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

Fisher, Robbert, Julien Chicot, Alberto Domini, Milica Misojcic, Gabriela Bodea, Kristina Karanikolova, Alfred Radauer, María del Carmen Calatrava Moreno, Lionel Bently, and Estelle Derclaye (24 April 2018). Study in support of the evaluation of Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978‑92‑79‑81358‑0. doi:10.2759/04895.

Fisher, Robbert, Julien Chicot, Alberto Domini, Milica Misojcic, Gabriela Bodea, Kristina Karanikolova, Alfred Radauer, María del Carmen Calatrava Moreno, Anna Gkogka, Lionel Bently, and Estelle Derclaye (24 April 2018). Study in support of the evaluation of Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases — Annex 1: In-depth analysis of the Database Directive, article by article. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978‑92‑79‑84964‑0. doi:10.2759/129814.

Fisher, Robbert, Julien Chicot, Alberto Domini, Milica Misojcic, Gabriela Bodea, Alfred Radauer, María del Carmen Calatrava Moreno, Anna Gkogka, Lionel Bently, and Estelle Derclaye (24 April 2018). Study in support of the evaluation of Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases — Annex 2: economic analysis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978‑92‑79‑84960‑2. doi:10.2759/48098.

Fisher, Robbert, Julien Chicot, Alberto Domini, Milica Misojcic, Gabriela Bodea, Kristina Karanikolova, Alfred Radauer, María del Carmen Calatrava Moreno, Anna Gkogka, Lionel Bently, and Estelle Derclaye (24 April 2018). Study in support of the evaluation of Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases — Annex 6: Bibliography. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978‑92‑79‑84962‑6. doi:10.2759/978921.

JRC (2018). European Commission Reuse and Copyright Notice (for the Joint Research Centre Data Catalogue). JRC, European Commission. Brussels, Belgium. Same notice also used by IDEES (Integrated Database of the European Energy System).

European Commission (10 January 2017). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: “Building a European data economy” — COM (2017) 9 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission. Contains the technical definitions given earlier.

European Commission (2017). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the mid-term review on the implementation of the Digital Single Market Strategy — A Connected Digital Single Market for All — COM/2017/0228 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (2017). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the mid-term review on the implementation of the Digital Single Market Strategy — A Connected Digital Single Market for All — COM/2017/0228 final — Annex. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (24 July 2014). “Commission notice: guidelines on recommended standard licences, datasets and charging for the reuse of documents”. Official Journal of the European Union. C 240: 1–10.

European Commission (17 July 2012). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions towards better access to scientific information: boosting the benefits of public investments in research — COM (2012) 401 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

European Commission (14 December 2011). “Commission decision of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents — 2011/833/EU — Document 32011D0833”. Official Journal of the European Union. L 330: 39–42.

European Commission (12 December 2005). First evaluation of directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases — DG internal market and services working paper. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

References and further reading

Anon (21 November 2017). A review of the ENTSO-E Transparency Platform: Output 1 of the “Study on the quality of electricity market data” commissioned by the European Commission. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission. Publication date from PDF metadata. From the cover, VVA, Copenhagen Economics, Neon, and Deloitte were involved.

Bertuzzi, Luca (3 February 2022). Industry readies to fight the Commission’s Data Act proposal. www.euractiv.com.

Bertuzzi, Luca (2 February 2022). LEAK: Data Act’s proposed rules for data sharing, cloud switching, interoperability. www.euractiv.com.

Cattaneo, Bruno (28 March 2019). Commission makes it even easier for citizens to reuse all information it publishes online. EU Science Hub — European Commission. Last update: 5 April 2019.

CJEU (3 June 2021). Judgment of the Court on ‘CV-Online Latvia’ SIA v ‘Melons’ SIA, case C‑762/19, document ECLI:EU:C:2021:434. Luxembourg City, Luxembourg: Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). 6 pages.

Davidson, Mark J (January 2008). The legal protection of databases. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978‑0‑521‑04945‑0. Paperback edition.

DeCarolis, Joseph F (5 February 2022). Opening Statement — Joseph F. DeCarolis — Nomination Hearing — United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Washington DC, USA: U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Document date from PDF metadata.

Drexl, Josef (2017). “Designing competitive markets for industrial data: between propertisation and access”. Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and E-Commerce Law (JIPITEC). 8 (1): 257–292. ISSN 2190‑3387.

Duch-Brown, Nestor, Bertin Martens, and Frank Mueller-Langer (2017). The economics of ownership, access and trade in digital data — JRC Digital Economy Working Paper 2017-01. Seville, Spain: European Commission JRC (Joint Research Centre) Technical Reports.

van Eechoud, Mireille (1 April 2021). “A serpent eating its tail: the Database Directive meets the Open Data Directive”. IIC — International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law. 52 (4): 375–378. ISSN 2195‑0237. doi:10.1007/s40319-021-01049-7. Editorial.

Higgs, Daphne and Pete Gutsche (29 September 2021). Show me the money: monetizing IP via licenses — Presentation. Washington, USA: Perkins Coie LLP.

Hirth, Lion (1 January 2020). “Open data for electricity modeling: legal aspects”. Energy Strategy Reviews. 27: 100433. ISSN 2211‑467X. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2019.100433. Open access.

Husovec, Martin and Estelle Derclaye (17 June 2021). Access to information and competition concerns enter the sui generis right’s infringement test – The CJEU redefines the database right. Kluwer Copyright Blog. Concerns case C‑762/19 and ruling ECLI:EU:C:2021:434.

Kerber, Wolfgang (September 2016). A new (intellectual) property right for non-personal data?: an economic analysis — Joint discussion paper 37-2016. Marburg, Germany: Philipps-University Marburg. ISSN 1867‑3678.

Negreiro, Mar (26 September 2018). Free flow of non-personal data in the European Union — Briefing — PE 614.628. Brussels, Belgium: European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS).

Osborn, Lucas S (2017). “The limits of creativity in copyright: digital manufacturing files and lockout codes”. Texas A&M Journal of Property Law. 4: 25.

Reda, Julia (2017). Learning from past mistakes: similarities in the European Commission’s justifications of the sui generis database right and the data producers’ right. In Sebastian Lohsse, Reiner Schulze, and Dirk Staudenmayer (editors). Trading data in the digital economy: legal concepts and tools. Pages 295–304. Baden‑Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlag. ISBN 978‑1‑5099‑2120‑1.

Smith, McCoy (no date). OSI permissive licenses: grammatical/textual analysis. USA: Intel Corporation. PDF forwarded by email. (OSI is Open Source Initiative.)

Stepanov, Ivan (2 January 2020). “Introducing a property right over data in the EU: the data producer’s right — an evaluation”. International Review of Law, Computers and Technology. 34 (1): 65–86. ISSN 1360‑0869. doi:10.1080/13600869.2019.1631621. Open access.

Tarkowski, Alek and Francesco Vogelezang (10 December 2021). The argument against property rights in data — Policy brief #1. Europe: Open Future. Creative Commons CC‑BY‑4.0 license.

Viljoen, Salomé (2021). “A relational theory of data governance”. Yale Law Journal. 131: 573. ISSN 0044‑0094.

Vollmer, Timothy (2 April 2019). European Commission adopts CC BY and CC0 for sharing information. Creative Commons.

Warnke, Philine, Kerstin Cuhls, Ulrich Schmoch, Lea Daniel, Liviu Andreescu, Bianca Dragomir, Radu Gheorghiu, Catalina Baboschi, Adrian Curaj, Marjukka Parkkinen, and Osmo Kuusi (3 December 2019). 100 radical innovation breakthroughs for the future — KI-04-19-053-EN-N. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978‑92‑79‑99139‑4. doi:10.2777/24537.

Wiebe, Andreas (1 January 2017). “Protection of industrial data: a new property right for the digital economy?”. Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice. 12 (1): 62–71. ISSN 1747‑1532. doi:10.1093/jiplp/jpw175.

Wiebe, Andreas (2016). Who owns non-personal data?: legal aspects and challenges related to the creation of new “industrial data rights” — Presentation. Göttingen, Germany: University of Goettingen. Slides presented at the GRUR conference on data ownership, Brussels.

Zech, Herbert (2015). “Information as property”. Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and E-Commerce Law (JIPITEC). 6 (3): 192–197. ISSN 2190‑3387.

▢